Foreign Languages

As part of the integral studies program, most Montessori Schools introduce a second language to even their youngest children. The primary goal in a Foreign Language program is to develop conversational skills along with a deepening appreciation for the culture of the second language.

Hands-On-Science The Montessori Way

Science is an integral element of the Montessori curriculum. Among other things, it represents a way of life: a clear thinking to gathering information and problem solving. The scope of the Montessori science curriculum includes a sound introduction to botany, zoology, chemistry, physics, geology and astronomy.

Montessori does not separate science from the big picture or the formation or our world. Students consider the formation of the universe, development of the planet Earth, the delicate relations between living things and their physical environment and the balance within the web of live. These great lessons integrate astronomy, the earth sciences and biology with history and geography.

The Montessori approach to science cultivates children’s fascination with the universe and helps them develop a lifelong interest in observing nature and discovering more about the world in which they live. Children are encouraged to observe, analyze, measure, classify, experiment and predict and to do so with a sense of eager curiosity and wonder.

In Montessori science lessons incorporate a balanced, hands-on approach. With encouragement and a solid foundation, even very young children are ready and anxious to investigate their world to wonder at the interdependence of living things, to explore the ways in which the physical universe works, and to project how it all may have come to be.

For example in many Montessori schools, children in the early Elementary grades explore basic atomic theory and the process by which the heavier elements are fused out of hydrogen in the stars. Other students study advanced concepts in biology, including the systems by which scientists classify plants and animals. Some Elementary classes build scale models of the solar system that stretch out a half-mile!

In Montessori, The Arts Are Integrated Into Every Subject

In Montessori schools, the Arts are normally integrated into the rest of the curriculum. They are modes of exploring and expanding lessons that have been introduced in Science, History, Geography, Language Arts and Mathematics.

For example, students might make a replica of a Greek vase, study calligraphy and decorative writing, sculpt dinosaurs for science, create dioramas for history, construct geometric designs and solids for math and express their feelings about a musical composition through painting.

Art and Music History and Appreciation are woven throughout the History and Geography curricula. Traditional folk arts are used to extend the curriculum as well. Students participate in singing, dancing and creative movement with teachers and music specialists. Students' dramatic productions make other times and cultures come alive.

Health, Wellness And Physical Education

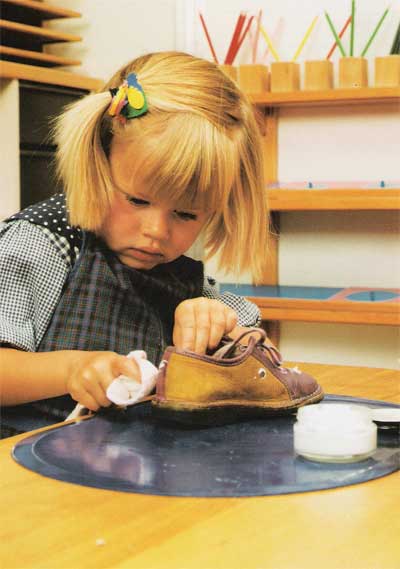

Montessori Schools are very interested in helping children develop control of their find and gross motor movements. For young children, programs will typically include dance, balance and coordination exercise, as well as the vigorous free play that is typical on any playground.

With Elementary and older students, the ideal Montessori Health, Physical Education and Athletics program is typically very unlike that of the traditional model of "gym". It challenges each student and adult in the school community to develop a personal program of lifelong exercise, recreation and health management.

Many schools have limited space and facilities, but where funds and facilities are available for older students, the ideal Montessori environment offers a variety of facilities and programs, which can potentially include a room with stationary bikes and other exercise equipment designed for children, an indoor track, a basketball court a room for aerobic dance and perhaps even an indoor pool and tennis courts.

Again ideally, this fitness center would not be reserved for the children alone; school families would be able to use the facilities after hours, on weekends and during school hours when it didn't interfere with student programs.

One important element in the Montessori approach to health and fitness is helping children to understand and appreciate how their bodies work and the care and feeding of a healthy human body. Students typically study diet and nutrition, hygiene, first aid response to illness and injury, stress management and peacefulness and mindfulness in their daily lives.

Daily exercise is an important element of a lifelong program for personal health, but instead of one program for all, students are typically helped to explore many different alternatives.

Students commonly learn and practice daily stretching and exercises for balance and flexibility. Some programs introduce students to yoga, tai chi, chi gon or aerobic dance.

Children learn that cardiovascular exercise can come from vigorous walking, jogging, biking, rowing, aerobic dance etc. through actively playing field sports like soccer or from a wide range of other enjoyable activities such as swimming, golf or tennis. With older students, the goal is to expose skills and helping them to develop a personal program of daily exercise.

We would like to express our thanks to the Montessori Foundation and Mr. Tim Seldin, President.